Granted, this approach might not be very scientific, but it can sometimes bring you close.

With this one I need to explain a little more than usual about the vehicle history. This car was a 1999 Ford Escort 4 cylinder 1.6 litre and had been bought by the new owner from a reputable used car lot with no apparent problem whilst at the lot. After a few weeks in the hands of the new owner, the car had an additional inventory of lowered springs, alloys, up-rated stereo, and two big holes in the rear parcel shelf ready for some speakers. One morning the vehicle owner came to start the car and it cranked but wouldn’t fire.

The car was returned to the sales lot where they spent some time on it but had no luck. It then got referred to a local garage where they managed to build a bigger picture about the fault. They found the car had spark at all four plugs, all four injectors were firing, fuel pressure was good, compressions were good, and it had a steady gas flow through the tailpipe; it seemed to have everything. There was a clue in that occasionally the engine would backfire together with a sudden crank rotation lock-up; both indicative of an ignition timing issue. The garage pulled the timing belt cover to check belt condition and mechanical timing marks, but all seemed OK. They changed the CKP sensor, fitted a different CMP sensor and a different coil pack, and a new ECM was next on the list. It was here that I got called in.

The garage also queried whether the OEM PATS immobiliser was having any influence. They were sure of a spark present at all plugs and the injectors were indeed firing. This, coupled with the fact that the PATS MIL wasn’t flagging a fault, didn’t at this stage give any cause for concern, so I moved on to other more likely areas. A point which everybody was sure about was that the car ran perfectly before the customer got his hands on it.

I felt that the garage was right on track with an ignition timing issue, but just hadn’t managed to pinpoint the fault yet. If there’s one thing I preach it’s always start at the beginning. If we are dealing with a timing issue, we need to look at when ignition is occurring and compare it to crank rotation and piston position.

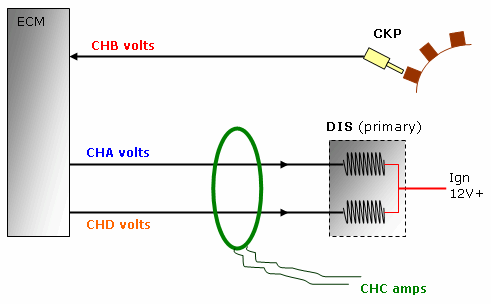

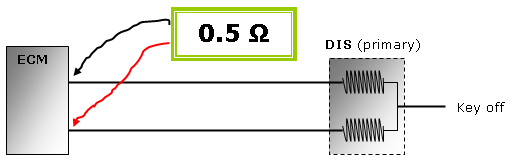

This engine uses a simple ignition system. The basis of its operation is that the ECM collects information from the CKP sensor and emits two separate primary dwell commands to a single DIS pack.

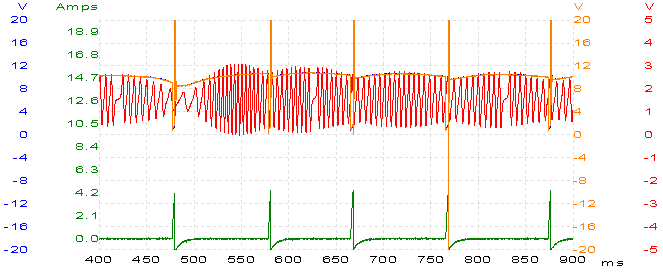

Figure 2

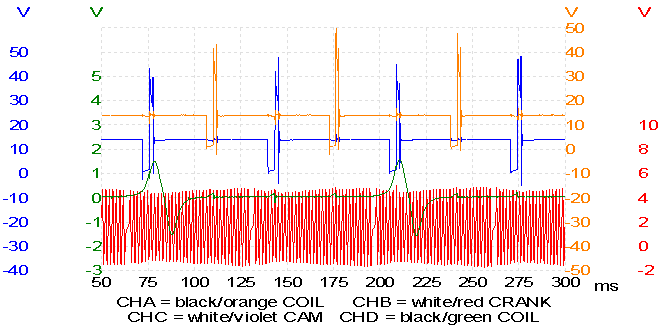

Figure 2 shows a typical capture with the engine cranking and our fault present. All trace captures were taken with the scope’s common (black lead) connected to the vehicle’s chassis ground. When capturing a trace, many people attach great importance to where to stick the red probe without giving proper consideration what to do with the black probe; yet the quality of the result relies equally on both probes.

Channel A (red) — We see a good crank rotation and speed with no obvious signal anomalies. This CKP circuit uses a variable-reluctance sensor with both attached cables carrying the AC generated signal. The circuit is biased at about 1.5 V to aid the ECM’s self-check. There are a few traps to beware of: most important is to make sure you are monitoring the correct cable, so that you keep the test results constant and reliable and always with the same trace polarity. Here both CKP cables will give very similar trace patterns, but one will be the inverse of the other and it’s difficult to tell which is right and which is wrong for a particular system. I probed the White/Red cable, compared it to a previously stored known good capture, and it checked out OK.

We also can get a good visual correlation as the engine attempts to lock from our suspected timing error.

Channel B (blue)— The trace is difficult to see but it is there, hiding behind the Channel D (orange) trace, which is odd. I would expect to see the dwell commands alternate between 1 and 4, then 2 and 3, and back to 1 and 4 with all commands being 180° apart with respect to crank position. According to the capture, the cylinder 1 and 4 dwell period is occurring at precisely same time as the cylinder 2 and 3 dwell period. It also seems that the reverse is true; 2-and-3 is occurring at the same time as 1-and-4. There’s something not right, and it confirms an ignition timing issue.

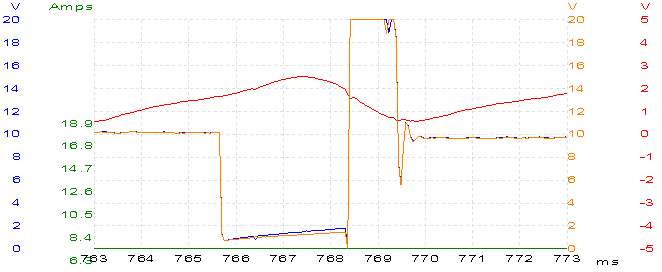

Figure 3

Figure 3 shows one of the primary ignition pulses from the previous capture in more detail. This is where the powerful zoom built in to the PicoScope software comes in handy.

Channel C (green) — At the time of hook-up I don’t know what I’m going to find, so it makes sense to get as big a picture as possible about what is going on, as sometimes only one channel trace may prove to be of any value. What clearly needs investigating further is the presence of both coil primary commands at the same time, causing plugs 1, 2, 3, 4 all to fire together. Does the ECM know it’s doing this? Some weird default strategy? Maybe the garage was right: a broken ECM.

I’ve touched on this subject before in other case studies: when a diagnosis is taking me down the road of a new control unit I get suspicious that there’s still something waiting to be found. The next step is to test the relevant cabling and attached components. As the circuit illustration earlier shows, this system is simple enough for us to work out a checking procedure. The ECM power supplies were checked and confirmed even though this really didn’t seem a likely cause of the fault — it was nevertheless still an important step. It wasn’t long, after collecting a few meter readings, that one particular resistance value didn’t seem right.

With key off, I checked the circuit resistance between one DIS primary cable and the other. Ordinarily I would err on the side of caution when taking resistance readings with a control unit still connected, because semiconductor susceptibility and meter polarity issues can give false meter readings and send you off on a two-hour ghost hunt. However, with this problem, it was important that I saw what the ECM was seeing. I expected a low reading somewhere in the region of 2 ohms, but my reading was too low.

Then, with the ECM isolated, I got the same 0.5 ohm reading, so this obviously eliminated the ECM as a possible cause. What nailed this fault was when I disconnected the DIS pack from the other end and got the same 0.5 ohm. The coil command lines were shorted together!

This now made perfect sense and tied cause and effect together nicely.

Figure 6 shows a hole that was discovered. This was drilled into the bulkhead — a popular place for routing extra power cables for in-car entertainment. Twisting round the engine harness revealed severe cable damage.

Figure 6.

Remember the customer’s additional inventory put on the car...

Stripping back the insulation I found that a lot of cable strands had suffered, which meant that new cabling had to be soldered in. With the repair in place, the engine fired up for the first time in weeks. From here on I recommended an oil and filter change to remove heavy fuel deposits from the weeks of cranking, and a decent run at cruise speed to clear out the exhaust stream and regain suitable closed loop and emissions. Figure 7 shows the patterns I was expecting to see earlier.

其它辅导资料 >

|